The Netherlands’ highest court has ruled that doctors can honour euthanasia requests for adults with advanced Alzheimer’s, provided they have signed a written request beforehand.

Although it has always been possible in the Netherlands for a patient unable to express their will at the moment of death, to receive assistance to die, this ruling has brought further clarity on the law there. Doctors will now be able to help under strict conditions, including that the patient must have ‘unbearable and endless suffering’ and that at least two doctors must have agreed to carry out the procedure. The patient must also have made a declaration that they want assistance before they could ‘no longer express their will as a result of advanced dementia’.

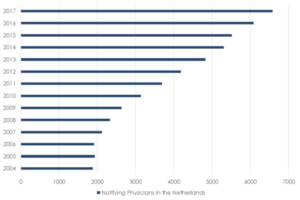

The latest figures show that the overall number of requests for assisted dying has fallen in the Netherlands, and only two people with severe dementia applied for an assisted death in 2018.

This ruling follows from an earlier decision in the Netherlands, which acquitted a doctor for helping a 74-year-old woman end her life. The woman, who had been suffering from severe Alzheimer’s, had written a statement saying she wanted to die if she became incapacitated.

Commenting on the ruling, Trevor Moore chair of the campaign group My Death, My Decision said:

‘Dying in a manner and timing of your own choice relates to the most fundamental of human rights – autonomy. No one should be forced to endure as an illness eclipses their very being or slowly erodes everything which once made them themselves. That’s why we support assisted dying for adults of sound mind who are either incurably suffering or terminally ill, and that’s why the law must change.’

‘However, we believe mental capacity is an essential safeguard within any system which permits assisted dying. We encourage everyone in the UK, suffering from Alzheimer’s, who wants greater control over their end of life care, to set out their wishes in an advance decision or through a lasting power of attorney.’

.

Recent Comments