MDMD has been following the story of Marieke Vervoort, the medal-winning paralympic athlete, since she announced her intention to end her life when she felt the time was right for her. Many papers, including The Guardian and The Mail have reported her death by euthanasia on 22nd October 2019. Marieke had endured unbearable pain as a result of the degenerative condition Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy, an incurable illness which can cause a burning sensation within the limbs, which even the best palliative care could not alleviate.

It is interesting to contrast the approach of palliative care options in Belgium with those in the UK. Marieke’s palliative care doctor gave her the best pain relief he could, but he could also provide euthanasia when asked. In this country that is impossible due to the law preventing medical assistance to hasten death. Instead, when asked how to avoid incurable suffering in the case of dementia, (and by implication other conditions such as Marieke’s where death could not be caused by refusing treatment), Baroness Finlay, Professor of Palliative Medicine at Cardiff University and a long-standing opponent of medically assisted dying, said “there’s no law against committing suicide”. How does she think one could do this? “There are people ordering drugs over the internet now and taking overdoses”, was her response. Attempting to wash their hands of the problem of incurable suffering, and pointing to unsafe and illegal suicide alternatives is not an acceptable position for the palliative care community. The law in Belgium allows palliative care there to set a much better example.

In an earlier interview, when Marieke had obtained papers authorising her assisted death, she said:

“Those papers give me a lot of peace of mind because I know when it’s enough for me, I have those papers… If I didn’t have those papers, I think I’d have done suicide already. I think there will be fewer suicides when every country has the law of euthanasia. … I hope everybody sees that this is not murder, but it makes people live longer.”

The fact that Marieke delayed her death for 3 years since publicly stating her intention to take the option available to her, clearly demonstrates this point. It shows that she took a long time to carefully consider her decision and to ensure that she lived her life as long as she could tolerate, with the help of the best that palliative care could offer. A recent report highlights the extent to which palliative care in the UK fails to relieve suffering at end of life – “17 people per day will suffer as they die”.

The BBC have an in depth interview with Marieke available on-line, recorded in 2016, where she discusses her sporting achievements, the challenges of living with her disability, and her clear wish to eventually have a medically assisted death.

In response to Marieke’s death Christian Today and The Independent Catholic News quote Gordon Macdonald, chief executive of Care Not Killing, who said “It is extremely sad news that Ms Vervoort has chosen to end her life this way, but her death highlights how the right to die has become a duty to die in both Belgium and their near neighbours in the Netherlands.” Really? A Duty? On what basis does he reach that conclusion? On the contrary, it seems clear from her interviews and quotes that far from feeling a “duty to die”, the euthanasia law in Belgium enabled Marieke to live for longer than she might have otherwise, and with the comfort of knowing that a peaceful death was available when she eventually needed it. Gordon Macdonald, in not welcoming the compassion available under Belgian palliative care in extreme situations like this, seems to be saying that Marieke had a “duty to suffer for longer”. MDMD together with the vast majority of the public, consider this position to be callous and medieval.

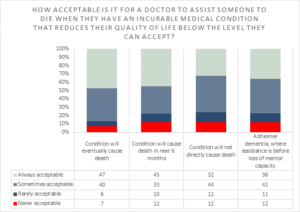

Graham Spiers, writing in the Times, who also comes from a Christian background, demonstrates a much more compassionate attitude when he says “The Church remains largely against assisted suicide, and with well meaning, but the prolonged, ceaseless, acute suffering of people has made it an impossible argument to sustain. To those, like Vervoort, who despite medicine’s best efforts, were often in excruciating pain, the Church was saying: ‘Bear with it. Hang in there. Don’t deny God. See it through.’ It is an abhorrent stance to adopt.” Fortunately, at least a few Christian leaders agree with Graham Spiers’ view, including Desmond Tutu, the ex Archbishop of Canterbury, George Carey and MDMD Patron and General Synod Member Rev Rosie Harper. Importantly, both George Carey and Rosie Harper recognise that assisted dying should be available for people who are suffering incurably, even if they are not terminally ill – people like Tony Nicklinson, Omid T, MDMD patron and campaigner Paul Lamb and of course, Marieke Vervoort. None of these people would be helped by an assisted dying law which only helped those with a life expectancy of 6 months or less – that criterion too has become “an impossible argument to sustain” and is “an abhorrent stance to adopt”, as Marieke Vervoort’s case demonstrates and as MDMD has always argued.

Recent Comments