The Observer recently published a story about Wendy Mitchell, an Alzheimer’s sufferer whose memoir, ‘Somebody I Used to Know’, has recently been published. The article gives in interesting insight into how Wendy copes with the devastating diagnosis of dementia at the age of 58. Wendy is described as an energetic single mother of two adult daughters who had worked as an NHS administrator.

The Observer story has some interesting parallels with the case of Alex Pandolfo who received his Alzheimer’s diagnosis when he was 61. Like Wendy, Alex was a capable, strong-willed professional, firmly in control of his own life and very unwilling to give up easily. Alex’s story, published in the Mail on Sunday in May 2017, was remarkable as he explained his decision to seek an assisted suicide in Switzerland rather than endure the final stages of dementia. Wendy, at least in the published article, does not appear to go that far in her thinking, but the article does say that “She hopes that death will come before she is dismantled by the illness, or that the law will be changed so she will be able to choose her time of leaving”. Both Wendy and Alex share a common desire for a self-determined, peaceful death, rather than having to live through the inevitable disintegration of their personality that they know the final stages of their disease will bring. Their desire is echoed, by the fictional lead character with early-onset dementia in the film Still Alice, considered to be “shockingly accurate” by fellow sufferers.

Dementia is now the leading cause of death in England and Wales. Although most cases are detected at a much older age than Wendy and Alex, 5% of dementia sufferers have early-onset dementia, and there are fears that this is an under-estimate of the true incidence.

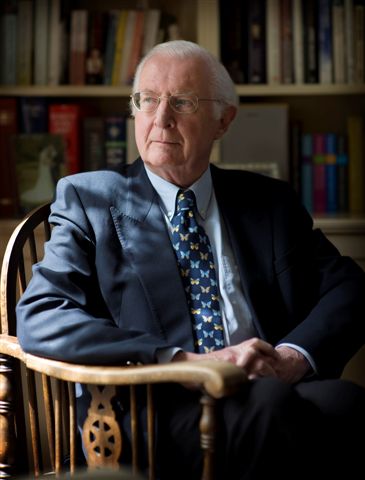

Following the article about Wendy, I talked again to Alex Pandolfo to see how his story is unfolding, and to look for parallels between his experience and Wendy’s.

A new sense of purpose

Wendy describes how she has managed to keep a positive approach to living with dementia through finding a new sense of purpose in publicising what dementia is like – her book is just one example of this which “has become her life’s work for as long as she is able to do it.” Alex has found similar outlets. No longer able to supervise university research, he devoted more time to his role as advocate for disadvantaged young people. As his condition worsened he had to stop this and is now concentrating on right-to-die campaigning – fighting for the right for people to have a medically assisted death, if that is their wish, and if their incurable illness causes them an unacceptably low quality of life – without having to travel to Switzerland, as Alex intends. He was advised to do something that he didn’t do before. “It’s important to keep my brain active and engaged” Alex says, “It gives my Alzheimer’s some value.” I’m not sure that right-to-die campaigning was quite what the professional who offered that advice had in mind, but it seems to serve the purpose.

Humour is important to both Wendy and Alex. Wendy finds it through contact with people in a similar situation to herself. This hasn’t worked for Alex. Instead he tells his friends “If you feel like taking the piss, take it” – a Mancunian who is proud of his abrasive northern wit.

I explored with Alex how things had changed since his Mail on Sunday article eight months ago. His view, that he wants to end his life in Switzerland before he is unable to live independently, has not changed, but he did admit to a “wobble” as he recovered from a minor stroke a few weeks ago. Fortunately, his previous mental capability has largely returned, but he describes his symptoms as having gone from “mild” to “moderate”. He notices his sense of time diminishing. He has to rely much more on alarms – something he never had to do. On the plus side, long train journeys can disappear in a flash.

Another change is more concerning. “I find myself getting angry so quickly. Something that I would have found innocuous now irritates me much sooner. I feel anger now like I’ve never felt in my life. That worries me.” Alex is so concerned by this development that he says this may make him take his trip to Switzerland sooner. He doesn’t want to end his life as an angry, possibly violent person. It wouldn’t be “him”.

Soon after his article was published last year Alex got the “green light” for his assisted death in Switzerland. (This means that the preliminary medical investigations have been carried out and the Swiss doctor has indicated that Alex’s conditions meet the criteria set by the legal and medical rules in Switzerland. Unlike the Bill rejected by the House of Commons in 2015, assisted suicide in Switzerland is not restricted to those who are terminally ill. Alex is free to arrange a date for his assisted suicide there when he likes – though additional checks at that time will confirm that he still retains sufficient mental capacity to freely decide to end his life.) How did he receive the news that he had the green light? “I can’t tell you how liberated I felt. Elated.” People told him he was looking better, healthier, and that he was presenting himself in a more positive way. “It really improved my feeling of quality of life.”

In the Mail on Sunday article about Alex, Dr Peter Saunders from the campaign group Care Not Killing, which opposes a change in the law on assisted dying, was quoted as saying “The best way to help dementia patients is to give them the best possible care.” Why does Alex think this wouldn’t be appropriate for him? “I really believe my independence is crucially important to me”, though he agrees that this is a personal decision and that good care should be available to those that would prefer it. He went on to describe in detail how his father suffered from a related illness. “I cared for my Dad with dementia, for five years. He was a strong man.” Alex explained how during his life his father had had to cope with both severe physical pain and many social difficulties. “He became incontinent. Every time he needed to be cleaned, tears ran down his face. No dignity. Whenever I showered him there were tears in his eyes. I did everything possible for him.” Alex was clearly emotional at the memory. We paused the conversation. “It was 13 years ago and I still get upset thinking about it”, Alex apologised. “I would not wish that on anybody, and I don’t want it for me. It is impossible to give good care to someone like that.”

Alex was full of praise for the attitudes of the healthcare professionals who have been treating him, despite them being unable to help him with his desire for a medically assisted death. “My GP has been 100% great.” After requesting a DNR and completing an Advance Decision, Alex mentioned his desire for an assisted death in Switzerland. “You do realise that I’m not permitted to discuss this, but I genuinely and honestly believe you should have the choice.” His GP told him.

When he was admitted to hospital, Alex was open with nurses, junior doctors and consultants about his plans for a good death in Switzerland. Everyone seemed to respect and understand his position. “I probably shouldn’t be saying this, but I totally agree with what you are saying” he was told by one of the professionals. It is surely unacceptable that our healthcare professionals are left afraid to discuss a patient’s end of life wishes with them if they involve, or may involve, an assisted death. Why no “patient-centred” care at this point? What damage might this be doing to the doctor-patient relationship, at a critical time in a patient’s life – even if the only medically-assisted options available are in Switzerland?

What is Alex finding more difficult to cope with now? “I’m becoming insular. I feel safe inside my house and am becoming uncertain about going out of the front door.” A keen Manchester City supporter – “This is probably my last season going to matches. The excitement just isn’t there anymore for me.”

Still happy? “Not as happy as I have been. I’m dwindling on a whole range of fronts.” But there’s still an optimism in his voice – “I’ve always been a problem solver – a do-er”.

After our conversation I’m left wondering if, and when, Alex will make use of his green light. Perhaps another unpredictable stroke will prevent him making the journey? – or his increasing fear of venturing outside will make the prospect too traumatic?

Alex is still very articulate in his speech, though his writing is more limited, and he complains of being less articulate than he was. “The words don’t come”, he complains. Wendy had assistance from a journalist in writing her book. Both seem to be impressive personalities, facing dementia with a positive attitude for as long as they can, determined to make a difference, right to the end… until the words don’t come anymore. But they don’t want to suffer the last bit… and if that is their choice, why should society make them?

Phil Cheatle

30th January 2018

Update March 2019:

Film maker Mark Scullion made a short film about Alex’s experience living with dementia. This sensitive film gives an insight into Alex’s personality and the difficulties of his condition. The film won the Royal Television Society Awards for Factual film 2019

Recent Comments