A new medical organisation in favour of assisted dying has been formed in the UK and will work to change the law on assisted dying to allow people in the UK who want the option of a safe and dignified assisted death.

Announced in a column in the British Medical Journal today, “MDMD Medical Group” (MD.MG)has been formed by a group of leading UK doctors. In the article, the best-selling author Dr Henry Marsh, women’s right advocate Professor Wendy Savage and acclaimed researcher Sir Iain Chalmers disputed claims that “pro-choice doctors” opposed changing the law on assisted dying, and called upon Parliament not to ignore the many people in the UK who want the option of a safe and dignified assisted death.

The new group, which is open to any pro-choice clinical professional, will be the first medical organisation in the UK advocating to allow mentally competent adults, who have incurable health problems and an intolerable quality of life, to have the option of a medically assisted death. The group will be Chaired by Dr Colin Brewer and joins the right to die organisation, My Death, My Decision.

In the letter, the three doctors write “as with earlier medical debates about contraception and abortion, [assisted dying evokes] strong feelings on all sides”, but, that, regardless of one’s view “the debate about legalising Medical Aid in Dying (MAID) in Britain is not going to stop”. They claim “whatever form legislation eventually takes, doctors will be the professionals most involved in enabling patients to have more control over the manner and timing of their death” and it is therefore essential for them to “revisit the fundamental issues of patient autonomy and choice”.

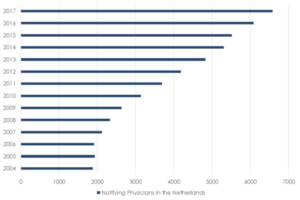

In a 2018 editorial, the British Medical Journal declared its support for changing the law on assisted dying and reported that over 55% of UK doctors agreed or strongly agreed that the law should change. A survey by Medix found that 45% of UK doctors believe that some healthcare professionals already assist with the death of patients.

The announcement comes after the Royal College of Physicians polled it’s members on whether it should change its policy on assisted dying reform, and news earlier this month that Jersey’s government will begin looking into whether the law on assisted dying should change.

Recently a new poll released by My Death, My Decision found that 93% of the public now consider assisted dying acceptable for those who are terminally ill in at least some circumstances, and 88% consider assisted dying acceptable for those suffering with Alzheimer’s in at least some cases, provided this was before they lose mental capacity.

Drs Marsh, Savage and Chalmers go on to say that “in Britain, and in several American states that have legalised assisted dying, there is a debate about whether the right to die should be restricted to patients with terminal illnesses, or be extended to those suffering from medical conditions that are intractable, intolerable and have no prospect of relief from an early natural death.” The letter highlights several British citizens in that category who have attracted “wide public sympathy and support”, such as Omid T who suffered from multiple systems atrophy and ended his life last October by medically assisted suicide in Switzerland, and Tony Nicklinson who suffered from locked-in syndrome and ended his life by starvation in 2012.

Following the High Court’s ruling against Omid T on a preliminary issue, and the Supreme Court’s decision not to grant Noel Conway permission to bring a case in December of last year, the group aims to encourage parliament to explore the “full spectrum of pro-choice views” and change the law to help those who are either terminally ill or incurably suffering”.

The new Chair of My Death My Decision Medical Group, Dr Colin Brewer has said:

“For some time now, doctors and nurses have watched with increasing despair, as the interests of their patients were sidelined and attempts to reform assisted dying faltered. All too often we have watched as debates about the right-to-die were confused by misinformation and myth. We believe it is now necessary for the voices of strongly pro-choice doctors and nurses to be heard. Our organisation hopes to provide a voice for those clinicians, and the balanced medical perspective that this debate has lacked.”

“The majority of doctors and nurses now believe that the law against assisted dying is unacceptable. Those who face incurable suffering as well as those who are terminally ill, deserve the option of a peaceful, pain-free and dignified death, but instead of strengthening the doctor-patient relationship, the law gags doctors and prevents them from engaging in open conversations.”

My Death, My Decision’s Director of Policy, Phil Cheatle, said:

“The fault lines in this debate have become clear. We know that an overwhelming majority of the public believe that the law on assisted dying should change, and that the medical profession stands with that of the compassionate majority. It is time for our decision-makers to heed their voices and legalise assisted dying, otherwise they will remain on the wrong-side of this debate.”

“My Death, My Decision welcomes MD.MG and is excited for such a distinguished group of clinicians to have joined our campaign for a more compassionate approach to dying in the UK. The current law prohibiting assisted dying is unacceptable. It is time for the UK to adopt a more compassionate law, which balances both the need for strong safeguards and a respect for human dignity.”

Recent Comments