Phil Newby, an incurably suffering father of two, has been denied permission to challenge the UK’s ban on assisted dying.

In a handed down judgment from the High Court, Lord Justice Irwin and Mrs Justice May ruled against permission to judicially review the UK’s ban on assisted dying.

A member of the right-to-die group My Death, My Decision and suffering from the degenerative condition motor neurone disease, Phil had already raised over £42,000 in donations from the public by the time of his judgment.

As a result of his condition, Phil is unable to dress himself, wash, hold a pen, or move beyond two rooms within his home without assistance. Seeking the right to control the manner and timing of his death, he had invited the court to examine a growing body of international evidence in support of assisted dying and asked or the right to cross-examine expert witnesses.

In the handed down judgment, the court said: ‘It is impossible not to have very great sympathy for the situation in which Mr Newby finds himself. His clear and dignified statement compels admiration and respect … Undoubtedly the HRA [Human Rights Act] has altered the relationship between the judiciary and Parliament. But this does not of itself impart or ascribe to the court expertise or legitimacy in the controversial questions of ethics and morals regarding the sanctity of life. These differences may mean that even in cases where the courts are empowered to act, they should be hesitant to do so.’

Ultimately holding that the High Court was bound by the Court of Appeal’s decision against Noel Conway in 2018, the Lord Justice Irwin and Mrs Justice May held:

‘The court is not an appropriate forum for the discussion of the sanctity of life, or for the resolution of such matters which go beyond analysis of evidence or judgment governed by legal principle. For these reasons, we refuse permission.’

If successful, Phil’s case would allow adults of sound mind the ability to request an assisted death, in circumstances where they suffer from an incurable disease which causes them unbearable suffering and cannot otherwise be palliated.

Trevor Moore, Chair of My Death, My Decision, who is supporting Phil’s case, added:

‘Now more than ever, as progressively more countries, including Canada, empower their citizens with the right to choose the manner and timing of their death, the nature of our country’s inexcusably callous law against assisted dying has become clearer. Public opinion has reached a watershed moment – nearly 90% now agree that adults of sound mind, who are either terminally ill or incurably suffering, deserve the right to a peaceful, painless, and dignified death. In light of that, it is hard to comprehend why the court has refused Phil Newby the opportunity to enable full scrutiny of the evidence, so that incurably suffering people like Phil, and Paul Lamb (who has also launched a legal challenge) have choice and control over how, when and where they die.’

Assisted dying is now permitted for terminally ill and incurably suffering people in Canada, Belgium, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. It is also permitted specifically for terminally ill people in Colombia, ten US jurisdictions, and the Australian state of Victoria.

NOTES

For further comment or information or requests for interviews, please contact My Death, My Decision’s Campaigns and Communications Manager Keiron McCabe at keiron.mccabe@mydeath-mydecision.org.uk or phone 020 7324 3001.

Details of the Case

Phil Newby, 49, a father of two from Rutland, was diagnosed with the progressive and degenerative medical condition, motor neurone disease in 2014. Unlike 2014, Phil had been working in the financial sector as CEO of Green Ventures. He is represented by Saimo Chahal QC of Bindmans LLP, Paul Bowen QC of Brick Court Chambers, Adam Wagner of Doughty Street Chambers, and Jennifer Macleod of Brick Court.

Phil is also being supported by the campaign groups My Death, My Decision (MDMD), Friends At The End (FATE), and Dignity in Dying.

If successful, Phil’s case would allow adults of sound mind the ability to request an assisted death, in circumstances where they suffer from an incurable disease which causes them unbearable suffering and cannot otherwise be palliated.

On 21 May 2019, Phil submitted an application to judicially review Section 2(1) of the 1961 Suicide Act. The court was invited to grant a declaration of incompatibility under the Human Rights Act 1998, on the grounds that the 1961 Suicide Act is incompatible with Phil’s rights under Article 2 (right to life) and Article 8 (right to a private and family life). In addition, the court was also invited to allow a preliminary issue of cross-examining expert witnesses to be appealed directly to the UK Supreme Court. On 27 September, the High Court handed down a judgment denying permission for the case to proceed.

On Tuesday 22 October, Phil’s legal team attended the High Court to appeal this decision. In a handed down judgment on Tuesday 19 November, Lord Justice Irwin and Mrs Justice May ruled that Phil Newby did not have an arguable case for permission to judicially review the Suicide Act 1961.

For legal comment or interviews with Phil Newby’s legal team at Bindmans LLP, please contact Saimo Chahal QC at s.chahal@bindmans.com or by telephone on +44 20 7833 4433

The law on assisted dying in the UK

Under section 2(1) and 2(2A) of the 1961 Suicide Act, it is unlawful in England and Wales to encourage or assist someone to end their life. Anyone found guilty of an act ‘capable of encouraging or assisting the suicide or attempted suicide of another’ can face up to 14 years’ imprisonment.

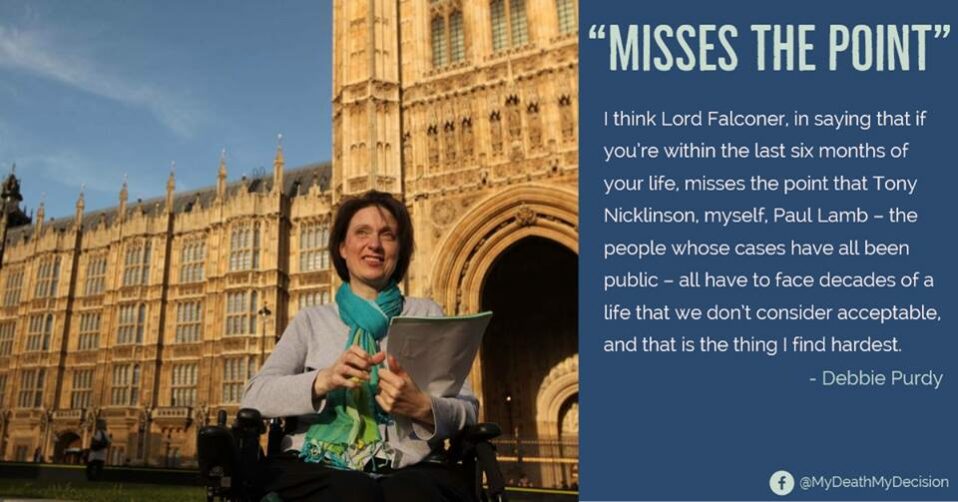

Following Debbie Purdy’s case, the then Director of Public Prosecutions, Sir Keir Starmer MP, issued guidance on factors indicating when a prosecution will and will not be brought for assisting another to die. One factor tending against prosecution is when a ‘suspect was wholly motivated by compassion’. Consequently, between April 2009 and January 2019, there have been 148 cases of assisted dying referred to the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) by the police, but only 2 successful prosecutions.

In 2014, Jane Nicklinson, the widow of locked-in sufferer Tony Nicklinson, and Paul Lamb, who is paralysed from the neck down, challenged the law on assisted dying in the Supreme Court. The court held that Parliament should be afforded the opportunity to debate the issue before the courts would rule on whether the law is incompatible with the rights of those who are both terminally ill and facing incurable suffering.

In 2015, parliament rejected by 330 against to 118 in favour, Rob Marris’ private members’ bill to legalise assistance for those who were terminally ill and likely to die within 6 months.

Under Section 1(2) of the 1982 Forfeiture Act, an individual who assists a loved one to end their life abroad can have their inheritance withheld, even if the CPS deems that it is not in the public interest to bring forth a prosecution.

Recent Developments

In November the UK’s largest medical association, the Royal College of GPs, opened their consultation on assisted dying.

In September, the Quebec Superior Court struck down a restriction under Canada’s law on assisted dying, against those with progressive and incurable illnesses. Following the judgment, unless the Federal Government challenges the decision within six-months, those with intolerable but non-life threatening conditions will be able to request an assisted death. Also in September, Italy’s constitutional court held that people should not always be punished for assisting another to die, if a person is in a state of intolerable and irreversible suffering.

In July, My Death, My Decision’s patron, Paul Lamb, who is paralysed from the neck-down, separately applied to the High Court to challenge the UK’s law on assisted dying.

In June, the British Medical Association announced that they would poll their members on assisted dying. Their announcement follows the Royal College of Physicians ending their long-standing opposition to assisted dying and adopting a neutral position in March 2019.

About My Death, My Decision

My Death, My Decision is a grassroots non-profit that campaigns for a balanced and compassionate approach to assisted dying in the UK. We believe that everyone deserves access to excellent palliative care but that adults of sound mind, who are either terminally ill or facing incurable suffering, should have the right to a peaceful, painless, and dignified death. Through the work of our members, supporters, patrons, and activists we help to broaden the public debate on assisted dying and seek to secure changes in the law.

Read more about how nearly 90% of the public support an inclusive change in the law.

Read more about how one Briton a week now ends their life in Switzerland.

Read more about My Death, My Decision’s campaign for an inclusive change in the law:

http://www.mydeath-mydecision.org.uk/

The Court of Appeal has rejected a bid from Paul Lamb to challenge the law banning assisted dying, in a judgment expected to end further legal cases for the foreseeable future. We are disappointed at the decision and urge Parliament not to allow this ruling to become the last word on assisted dying.

The Court of Appeal has rejected a bid from Paul Lamb to challenge the law banning assisted dying, in a judgment expected to end further legal cases for the foreseeable future. We are disappointed at the decision and urge Parliament not to allow this ruling to become the last word on assisted dying.

Germany’s constitutional court has ruled that a law forbidding professional assistance to die is unconstitutional, in a move that is being seen as a major victory for assisted dying campaigners.

Germany’s constitutional court has ruled that a law forbidding professional assistance to die is unconstitutional, in a move that is being seen as a major victory for assisted dying campaigners.

Recent Comments