MDMD’s Campaigns and Communication Manager, Keiron McCabe, breaks down the judgement behind Omid’s defeat.

On Tuesday 2nd October 2018, Omid T’s assisted dying case , known as R (on the Application of T) v Ministry of Justice [2018] EWHC 2615 (Admin), lost at its first hurdle in the High Court.

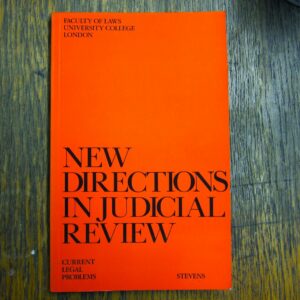

In order to challenge the UK’s prohibition of assisted suicide, it was necessary for Omid to bring a judicial review. This is the process in which the courts appraise the validity of a law based on a number of strict criteria, one example being a disproportionate infringement of the Human Rights Act 1998. Omid’s legal team argued because terminal and incurably suffering patients cannot access an assisted death, their rights to a private and family life were infringed and Section 2(1) of the Suicide Act 1961 must be declared incompatible with Omid’s human rights. In some respects this meant that Omid’s case was similar to Tony Nicklinson’s 2012 case , though different from Noel Conway’s current appeal which only focuses on the rights of terminally ill patients.

However, prior to its ruling, Omid’s case had acquired a considerable interest from the legal community because of its unique evidenced-based approach. Usually judicial reviews do not deal in evidence. It is assumed a review is merely on a matter of law as the facts are agreed in advance. Indeed the UK’s civil procedure rules, the rules which guide conduct in the courts, make no mention of evidentiary rules such as cross-examining witnesses for judicial review – it is a rarity, granted only at the discretion of the courts.

Omid’s case garnered such an intense interest precisely because it was attempting to argue that the UK’s law infringed human rights based on evidence. In doing so, Paul Bowen QC, Omid’s lawyer, was seeking to emulate the Canadian case “Carter v Canada”, which legalised assisted dying when the Supreme Court of Canada found as a matter of fact:

“no evidence from permissive regimes that people with disabilities are at heightened risk of accessing physician-assisted dying;”

“no evidence of inordinate impact on socially vulnerable populations in permissive jurisdictions;”

“no compelling evidence that a permissive regime in Canada would result in a ‘practical slippery slope.’”

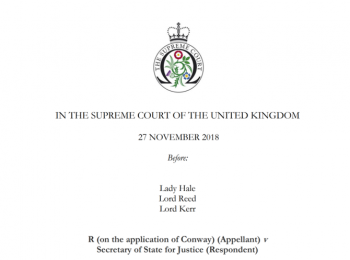

Considering the profound implications such an approach would have had on the right to die in the UK, the courts decided before commencing a full 3-4 week examination of the evidence, Omid had to prove that his case should be granted the rare discretion to cross-exam witnesses. However, it was agreed since the Court of Appeal may hear relevant issues whilst it was separately dealing with the Conway case, that the High Court would not pass judgement on the Omid case until afterward Conway.

“In my view, there is no moral or legal justification for drawing the line at terminal illness or 6 months or fewer to live. This would not have helped Debbie Purdy, Tony Nicklinson or me or many others who are begging for help to end our lives at a time of our choosing without pain in a dignified way.” – Omid T

Last Tuesday, Lord Justice Irwin, with whom Mr Justice Phillips agreed, ruled that Omid’s legal team did not have permission to cross examine the main witness, Baroness Finlay, and the case therefore could not progress to a full judicial review.

Omid’s ruling itself was somewhat complicated by the Conway case, as it was held that the evidence in the two cases “overlapped in great measure” . Indeed, Lord Justice Irwin went further and foundthat even though Conway’s case only focused on terminally ill patients, there was not a “material distinction” in the evidence between Conway and Omid’s appeals. This was because the evidence used for Omid’s appeal included information about jurisdictions in which assisted dying is only legal for those who are terminally ill and not both terminally ill/incurably suffering.

Additionally, Paul Bowen QC conceded, that following Conway, the evidenced-based approach of Omid could not succeed because the High Court would be “bound to find against [Omid]”.

However, even disregarding that concession, Lord Justice Irwin stated that he would have “reached the same conclusion in any event”.

Fundamentally, Lord Justice Irwin rejected the notion that a legal case on assisted dying could be assessed on the basis of factual evidence alone. He held that: “There exist facts bearing on the issue in question, and there are also a range of questions not reducible to hard fact, about which opinion must be formed and considered. The content of a study of impact of the legislation of euthanasia in the Netherlands is principally a question of fact. The methodology, rigour and accuracy of the conclusion of such a study is properly a question of expert opinion. The implications of such a study for the outcome of any english legislative change consequent on a declaration of incompatibly is not a ‘fact’, but a question of judgement about the future, and moreover is arguably a question beyond the special expertise of some (or perhaps all) of the instructed experts.”

He further stated that he did not have “any clear idea what…would be gained by oral evidence”, as opposed to second hand evidence such as published reports, and concluded “…the factual foundations for the views of various experts are either already clear, or can be clarified…based on written material…Mere differences of opinion or judgement will be evident from the existing reports and should not be the subject of further exchanges”.

As a final matter, Omid’s lawyers argued that even if their evidenced-based approach was bound to fail, the terminal-incurable distinction between Omid and Conway’s cases meant that Omid faced a strong chance along a more traditional judicial review route. Hence they requested for Omid’s case to be “leapfrogged” to the Supreme Court. This would mean, that instead of having to appeal to the Court of Appeal and then to the Supreme Court, Omid’s case could have been heard directly by the most authoritative court in the UK. However, Lord Justice Irwin considered this request to be “premature” and decided that Omid’s legal team could not start asking for their case to progress before it had even been given judgement. Lord Justice Irwin offered a glimmer of hope by suggesting that if the team wanted to continue, he would “do what is possible to facilitate speedy hearings for any further applications”. However, this prospect is very unlikely given that Omid sadly ended his life(link to previous Omid ends life article) at the Swiss Lifecircle clinic 5 days before the court gave its judgement. Omid’s case is therefore without a claimant, and its future is unknown.

Lord Justice Irwin’s reluctance to grant Omid an evidenced based review, though disappointing, is understandable. The High Court is a relatively junior court in the UK judicial hierarchy and at the most senior level, Assisted Dying has proven itself to be an issue of immense complexity for the Supreme Court. Hence it is understandable, faced with such a momentous decision, the High Court erred on the side of caution.

However, My Death, My Decision does not think the High Court reached the correct conclusion. In 2017, before she was recently appointed to the Supreme Court, Lady Arden, delivered an excellent speech on the issues of patient autonomy and medical law. In that speech, Lady Arden recognised that sometimes, on issues of particular importance, the UK courts may have additional responsibilities in conducting a judicial review. She said when a topic is so important, as Assisted Dying is, that Parliament will likely look to the courts, for some assistance, the courts may be required to examine information “in greater detail than it would have done before … and [deliver] a special type of judgement”. Similarly, in a 2015 case , decided above the High Court in the Court of Appeal, Lord Justice Lewison said that if the “justice” of a special case required a fuller examination of evidence, a court may permit the use of cross examination within judicial review.

Reflecting on these statements, it is clear that the ethical and moral implications of Assisted Dying mean it is a topic of special importance. Assuming that Parliament will turn to the courts for help, the justice of Assisted Dying must require our courts to conduct an investigation on fullest possible terms. Cross examination is a necessary part of that greater investigation. Unlike carefully crafted statements, cross examination is a candid process. For example, an expert who presents evidence may be sensitive to avoid inconvenient or inconsistent information within a written statement. Yet, when an expert is asked to confront their own inconsistencies or to address moot issues which may undermine their argument, such problems cannot so easily be avoided.

Alternatively, those who support the Omid ruling could argue that a good lawyer should spot these inconsistencies anyway and could bring them to the attention of the court themselves. Yet, Lord Irwin rightly said this approach would not be good. A good lawyer will only ever be able to spot such problems due to advice from a different expert and judges already know such differences of opinion between experts. Additionally, judges are shrewd professionals and are well trained to listen skeptically to the arguments of good lawyers. However, they may be more willing to defer to the credentials of an expert. Cross examination is therefore an important tool to assess the strength of an experts evidence. Whilst lawyers may, to some extent, be capable of clarifying issues, they will never speak with the same authority as someone can about their own evidence.

My Death, My Decision believes any debate on Assisted Dying should be based on the fullest of evidence available. Whilst Omid’s case may be disappointing, it was not brought in vain. Omid highlighted the intellectual inconsistencies in advancing a right to die merely for those with a terminal illness. Moreover, if nothing else, the ambition of Omid’s approach may yet bear fruit, as if Conway moves to the Supreme Court and Lady Arden is sitting, a fresh opinion on the value of an evidenced based approach may yet still be possible.

Recent Comments